Standing at the base of a 10,000 to 15,000-word dissertation can feel like looking up at Mount Everest. For most university students, this is the single most significant piece of independent research they will ever conduct. It is the “grand finale” of your degree, the project that proves you have shifted from being a student who consumes knowledge to a scholar who creates it. But a first-class dissertation isn’t just about having a brilliant idea; it is about how you house that idea. Without a rock-solid structure, even the most groundbreaking research can get lost in a messy, confusing narrative.

Many students struggle to balance the heavy word count with the need for academic precision, often feeling overwhelmed by the sheer volume of data and citations required. If you find yourself stuck at the starting line, seeking professional dissertation help from experts like myassignmenthelp can provide the structural roadmap and clarity needed to transform a chaotic draft into a polished, high-scoring academic masterpiece. Success in this arena is less about “working harder” and more about “working smarter” by following a proven architectural framework that examiners love to see.

Secret 1: The Introduction is a Contract, Not Just an Opening

The first secret to a top-tier dissertation is understanding that your introduction is a formal contract between you and your reader. You aren’t just saying “hello”; you are defining the boundaries of your world. A first-class introduction must do three things: establish the context (why does this matter?), identify the gap (what is missing in current research?), and state the aim (how will you fill that gap?).

Think of it as a funnel. You start with the broad landscape of your field and then narrow down sharply to your specific research question. If your introduction is vague, the examiner will spend the rest of the paper trying to figure out your point, which is a surefire way to lose marks. Clear, concise signposting where you literally tell the reader what each chapter will contain acts as a GPS for your academic journey.

Secret 2: The Literature Review is a Conversation, Not a List

The biggest mistake students make is treating the Literature Review like a shopping list: “Author A said this, then Author B said that.” To get a first-class grade, you must move from description to synthesis. You are the host of a dinner party where all the top experts in your field are invited. Your job is to facilitate a conversation between them.

Does Author A agree with Author B? If they disagree, why? Perhaps their methodologies were different, or they studied different demographics. Your goal is to show the “landscape of thought” and then find a hole in that landscape where your research fits. This demonstrates critical thinking—the hallmark of a top-tier student. You aren’t just reading books; you are evaluating the very foundations of your subject.

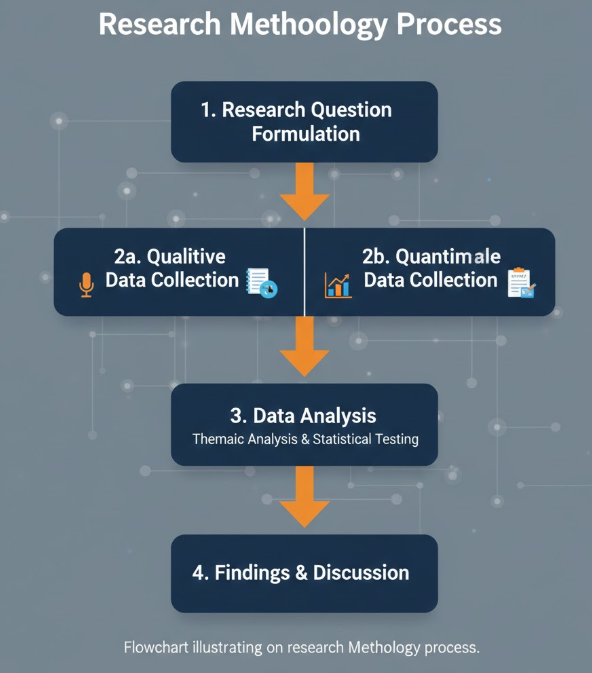

Secret 3: Methodology is the “Trust” Chapter

The methodology is often the driest part of the dissertation, but it is the most important for your credibility. This is where you prove that your results weren’t just a lucky guess. You need to justify every choice: Why did you choose qualitative interviews over quantitative surveys? Why was your sample size 50 and not 500?

A first-class methodology doesn’t just describe what you did; it defends it. You must address the limitations of your approach honestly. By showing that you understand the weaknesses of your research design, you actually make your findings more “trustworthy” in the eyes of the marker. You are showing that you understand the “rules” of science and scholarly inquiry.

Secret 4: The Power of the Presentation and the First Impression

Before an examiner reads a single word of your methodology, they see the layout. If your document looks like it was thrown together in a hurry, they will subconsciously expect the research to be sloppy too. This starts with the very first page. Ensuring your Dissertation Title Page Format is perfect—following your university’s specific guidelines for font, spacing, and institutional branding—sets a professional tone that persists throughout the paper.

Secret 4: The Logic of the Results and Discussion

Many students confuse the “Results” section with the “Discussion” section. In a first-class dissertation, the Results chapter is objective—it is just the facts, the charts, and the data. The Discussion chapter is where the “magic” happens. This is where you interpret the data.

The secret here is to link your findings back to the Literature Review you wrote earlier. Did your results confirm what Author A said, or did you find something completely different? If your results were unexpected, don’t hide them! Explain why they might be different. An “unexpected” result explained well is often worth more marks than a “perfect” result that was easy to predict.

Secret 5: The Conclusion – Leaving a Lasting Impact

The final secret is the “So What?” factor. A weak conclusion just summarizes the chapters. A first-class conclusion explains the significance of the work. If your research was implemented in the real world, what would change? What should the next researcher study to build on your work?

You want to end on a high note, leaving the reader with the feeling that they have just read something that actually matters. Avoid introducing any new information in the conclusion. Instead, tie all the loose threads together into a neat, strong knot. It is your final chance to prove that you have met the “contract” you signed in the introduction.

Detailed Chapter Breakdown for a 1,400+ Word Perspective

When writing a long-form dissertation, you must manage your word count like a budget. If you spend too much on the introduction, you won’t have enough “currency” left for the analysis. Here is a standard distribution used by high-achieving students:

- Introduction (10%): Setting the stage and the research question.

- Literature Review (20-30%): Evaluating existing knowledge and finding the gap.

- Methodology (10-15%): The “how” and the “why” of your data collection.

- Results (10-15%): The raw data and findings presented clearly.

- Discussion (25-30%): The deep dive into what the data actually means.

- Conclusion (10%): Summary, limitations, and future recommendations.

Practical Tips for Maintaining Focus

- The “Reverse Outline”: Once you finish a draft, write a one-sentence summary of every paragraph. If the sentences don’t flow logically, your structure is broken.

- Signposting: Use phrases like “Building on the argument in Chapter 2…” or “In contrast to the findings in the previous section…” This keeps the reader oriented.

- Peer Review: Sometimes you are too close to your own work. Have someone else read your headers. If they can understand the “story” of your dissertation just by reading the table of contents, your structure is strong.

The Role of Academic Integrity and Support

Writing a dissertation is a test of endurance. It is normal to feel lost in the middle of the “academic woods.” High-achieving students often use every resource available to them, from university writing centers to specialized online platforms. Whether it is refining your data analysis or ensuring your bibliography is flawlessly formatted, getting a second pair of eyes on your work is a sign of a serious scholar, not a struggling one.

By mastering these five structural secrets, you move away from the “hope for the best” strategy and toward a “guaranteed quality” framework. A first-class dissertation is not an accident; it is a carefully constructed building where every brick—from the title page to the final period—is placed with purpose.

Frequently Asked Questions

How should I divide my total word count across different chapters?

A balanced approach typically allocates 10% to the introduction and conclusion, 20-30% to the literature review and discussion, and the remaining 15% each to methodology and results. This ensures your critical analysis receives the most attention.

Can I use the same sources in my introduction and literature review?

Yes, but their purpose changes. In the introduction, sources establish the broad context and importance of the topic. In the literature review, you must critically analyze and compare those same sources to identify specific gaps in existing research.

What is the difference between a research aim and a research objective?

An aim is your broad, long-term goal—the “big picture” of what you want to achieve. Objectives are the specific, measurable steps or “mini-goals” you will complete to reach that overall aim.

Should I include my raw data in the main body of the text?

No. The main chapters should only contain analyzed data, such as summarized tables or key graphs. Raw data, like full interview transcripts or extensive survey spreadsheets, should be placed in the appendices to keep the narrative flow clear.

About The Author

Mark is a dedicated academic consultant and regular contributor at myassignmenthelp, where they focus on demystifying the complexities of higher education. With a passion for student success, Mark provides practical strategies to help scholars navigate their most challenging projects with confidence and clarity.